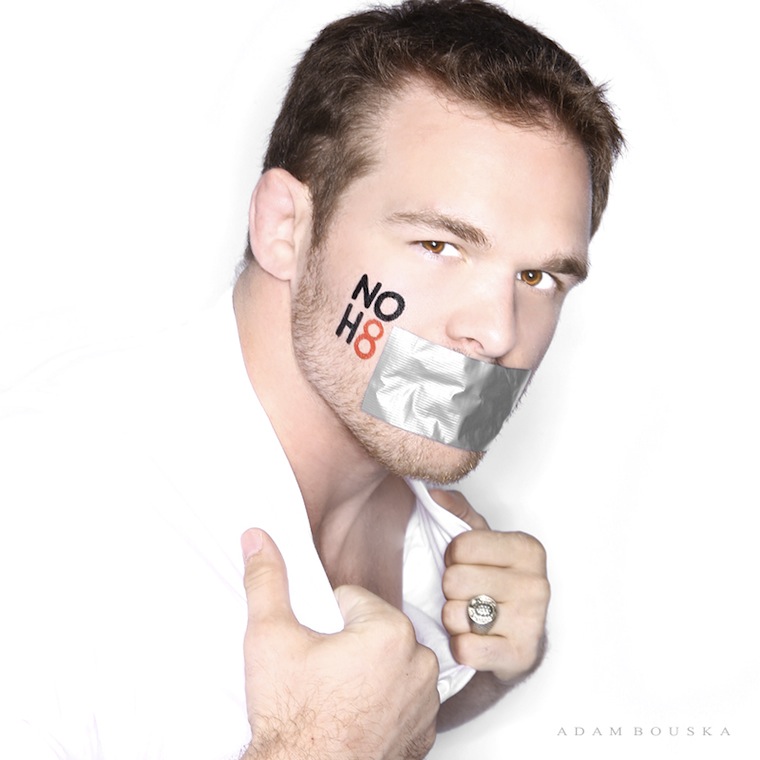

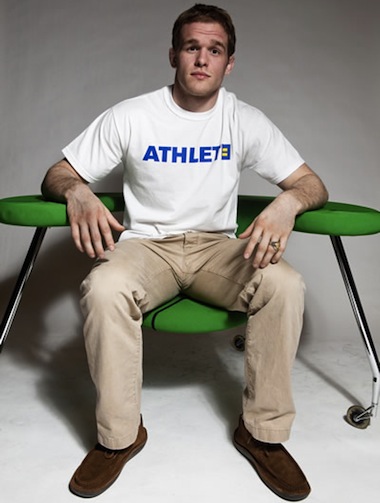

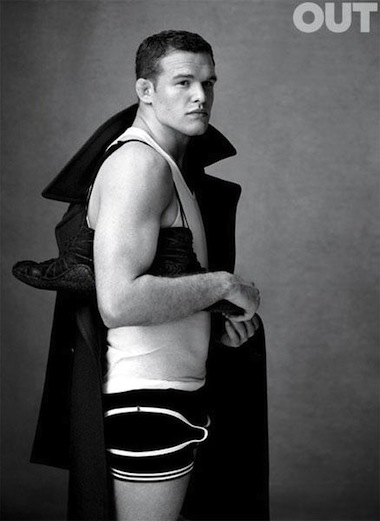

First, there is that physique. Strong, broad shoulders, thick, muscled thighs – it is the sculpted body of an athlete in peak form. Second, there is that face. Puppy dog eyes that make all the girls (and more than a few of the boys) swoon in dreamy abeyance. Third, there is that skill – the years of honed muscles, practiced execution, intensity and focus. The championships, trophies and medals proof of his excellence, his current position as coach proof of his endurance. Finally, there is that soul – the spirit that has given rise to such a movement – a revolution in effect – the starting motion to a generation of acceptance. The athlete, then, at his prime. He has nothing left to prove, and yet he strives for justice and equality. This is the hope of the future, and no one embodies that more than Hudson Taylor.

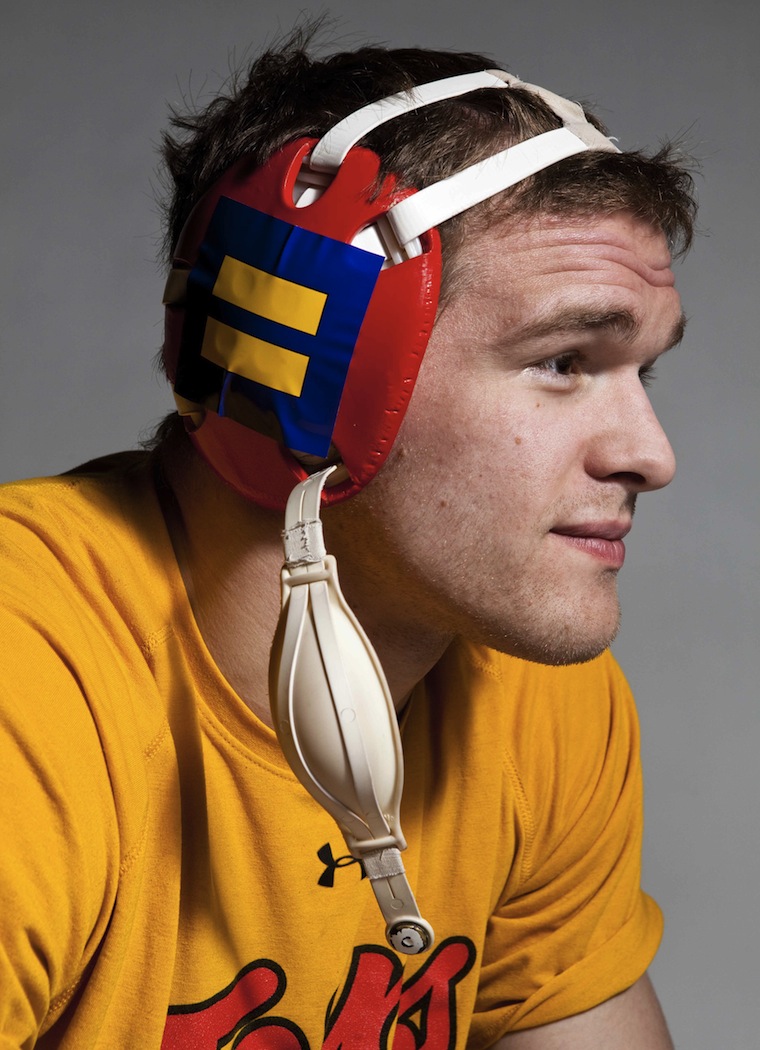

Taylor is the founder of Athlete Ally, an organization that aims to support inclusion and make all sports a safe playing ground for all people – particularly LGBTQ athletes. As the Executive Director, he also acts as the face of the mission, traveling to colleges and spreading his message in person. Eloquent and articulate, Taylor talks of “educating and empowering straight allies†and “creating an inclusive culture.†These are powerful, deep-reaching words, the manifestation of which could mean more for a cultural shift in eradicating homophobia than countless gay pride parades.

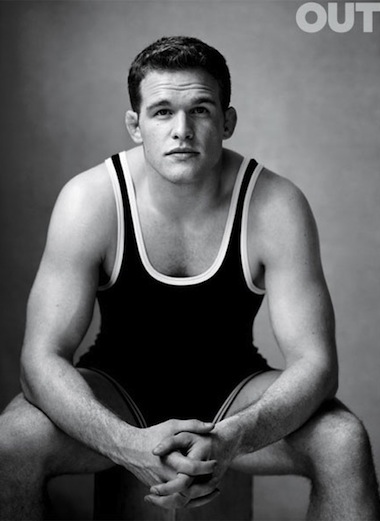

It’s one thing for a straight sports star to stand up at the end of his or her career and champion LGBTQ rights – it’s quite another for someone just starting out. That takes quite a bit more bravery, a courageous commitment, and a steely resolve. They are the real champions, they are the true heroes. Hudson Taylor did that on the college circuit – an almost-unthinkable act of bravery and courage that most of us can only imagine mustering.

On the larger celebrity scale, there are few straight men who have taken up the mantle of equality, especially in the sports world. One of the main tenets of being popular is to maintain a mainstream fan-base. We don’t want our sports stars to be all that different from us, except in the way they play the game. Yet every once in a while someone stands up for those of us without a voice and gives their support to our cause. They openly condemn homophobia, and fight for equality across all their public forums.

Coming from a straight athlete, the message can be of greater consequence. When a gay person fights for his or her rights, it’s the expected, obvious, and assumed stance. In a sense, it means less coming from one of us. But in the mouth of someone like Mr. Taylor, it gains something different, something more penetrating and significant. To a gay kid, it’s the voice of reassurance and affirmation from the majority, a message of inclusion, the emboldening feeling of love in realizing that there is, indeed, a place for us – all of us.

“I’m OK with people thinking I’m gay, because I know I’m doing the right thing,†Taylor says. It’s familiar territory for any straight ally: the assumption that only a gay person can fight for equality. It’s also the mark of someone supremely self-aware that others’ assumptions mean nothing in the face of what is right and just and true. It should come as no surprise that Taylor, along with having the soul of a poet, also has the soul of an artist. Aside from majoring in Performance Art, he dabbles in photography, experiments with imagery, messes around with Photoshop, and occasionally sings on YouTube (a sweet version of ‘Piano Man’.) He also has a magic touch – literally. Magic tricks – sleights of hand, particularly involving cards – are a favorite hobby, and he finds they work brilliantly as ice-breakers. Not that he needs any sort of social lubrication whatsoever: he speaks on a busy circuit, traveling and giving talks across the country, where his engaging presence breaks down centuries of barriers and resistance.

Most of us don’t have as open and accepting a mind and heart as Taylor has demonstrated from a young age. We close ourselves off to difference, we get comfortable in our own little cliques, and we surround ourselves with similar people. I’m guilty of it myself, and I’m always fascinated and impressed by those who look outside of themselves to find ways of connecting to people who aren’t necessarily like them. Taylor has mentioned that his father instilled a sort of moral compass in him, an integrity that could be found in sports, and he took that idea and ran with it.

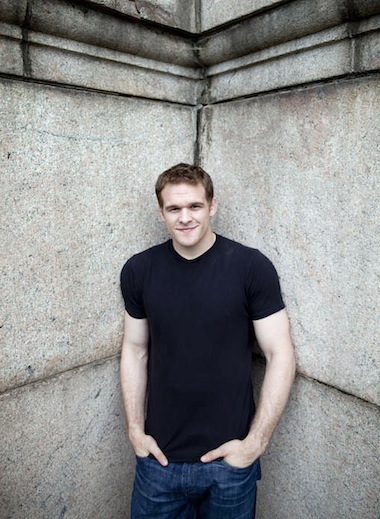

A few months ago, the Winter Olympics took place in Sochi, Russia, which was instantly condemned for its anti-gay legislation. Taylor was there in the thick of it, spreading his message of acceptance and inclusion in a peaceful yet effective way. His analysis on the importance of diversity among athletes was especially moving. It reminded me of the thrill I’ve always felt when watching the athletes march in the opening ceremonies of the Olympics. There’s something very reaffirming about seeing all the countries of the world come together in the name of athletic competition. According to Taylor, “Athletes become worthy of the greatest respect not when they win at their sport but when they stand up for the dignity of others and represent something bigger than themselves.†It was about respect and honor, and this was a part of sports that was rarely talked about, but proved integral to success both on and off the field.

Athletes in this country are revered and idolized, from the top-grossing baseball player to the ten-year-old girl on the local soccer team. We adore our athletes, and look to them, whether it’s right or wrong, to be an example and an inspiration for the rest of us. When I think back to high school, I remember the power and sway the football players had. Many boys looked up to them, many girls wanted to date them, and most of the teachers loved them. They were respected, honored, and, most importantly, heard.Â

Yet I avoided sports like the plague, even the repeated recruiting efforts of the track coach and the tennis coach and the swim coach, and, yes, the wrestling coach. The latter cornered me a few times, most likely looking for someone in the ultra-light-weight class. When I voiced my trepidations (I’m too weak, too small, not-athletic enough) he countered at every excuse, and even went so far as to appeal to my intelligence. Wrestling is one sport that is largely played out in the head, requiring strategy and quick-thinking, he said. The smartest kids made the best wrestlers. It almost worked, but I wasn’t buying it. I ran the risk of getting a beat down every day I wore whatever I wore to school – I didn’t need to guarantee a scheduled one.

I’m not delusional, and I can’t pretend that my sexuality alone kept me from playing; my disinterest in sports was probably less a fear of my homosexuality and more of an interest in just about anything else. Yet looking back, I now wonder if the excessively-macho attitude of the sports world kept me even more at bay. As a small, slight kid, I was scrappy yet coordinated. I could hit a mean softball, was always one of the last ones standing in any dodge-ball game, and climbed up to the top of the gymnasium on those big thick ropes. What I lacked in brawn I made up for in speed, agility and accuracy. I’d rather be lounging by the pool on any given day, but if need be I could smoke most of my classmates in a few laps. In other words, I’ve always been pretty fit, I just never quite fit in. Sports scared me. The locker room talk, the incessant teasing, the macho atmosphere that seemingly left no place for those with the slightest sense of sensitivity – taken together they conspired to instill a sense of fear. Had I heard someone – anyone – say something the least bit encouraging, an offer of the slightest solidarity, inclusion, or support, I might have stepped onto the track team, or picked up a tennis racket, or dove into the pool. Instead, I feigned loftier goals until I convinced myself of them.Â

When I listen to Hudson Taylor, I remember the scared boy I used to be, and I think how wonderful it would have been to hear someone say there was room for me on the team. That’s all any of us wants to hear. It’s what we need to hear. I’m grateful that there are people like Hudson in the world today, people who have the courage and the conviction to give a voice to those of us who aren’t quite sure we can use ours.

“When we diminish others, we only diminish ourselves.†~ Hudson Taylor

{Previous Straight Ally Profiles include Scott Herman and Skip Montross.}

Back to Blog