Everyone deals differently with death. For most of my life, I’ve shied away from it, changing the topic whenever it came up and actively dismissing it from my mind. The thought of losing someone I loved was too terrifying to do anything else. It was my way of coping with something that felt insurmountable. When Dad started to decline several years ago, I had to face it, whether I liked it or not, and it wasn’t easy.

His journey was a long one, and in many ways that helped. We had time together – time to become closer and talk before it became impossible, time to confront what was happening as every door closed and options dwindled. I had a good few years of dealing with impending death, so when it finally happened, I was as ready and prepared as one can be, even if one can never truly be ready for that. During his last two weeks on earth, I embraced the process as best as I could, managing to find the beauty and grace in what was happening, and finding solace in family, and the love that would continue even after his physical form departed.

Last weekend marked the two-month point since he died – something I hadn’t taken notice of – and I found myself in Amsterdam dropping off some food for Mom. Dad’s cemetery marker had been engraved and up for a few weeks, but I hadn’t been to visit. It was something I was consciously avoiding. Part of me was waiting to make it meaningful, to visit with intent and purpose, but as I left Mom’s, dirty and sweaty from putting up some fall decorations, I found myself turning down the road to the cemetery, almost without thought.

The afternoon sun hung just above the tree-lined horizon, dappled and divided through evergreen boughs. It was warm, and it was the last day of September. Turning into the cemetery, I passed rows of gravestones, looking at the various names, wondering at the families and the people who carried those names onward. There were names I recognized, though I’m sure not all were related to the people I knew. At the bottom of the hill, I stopped the car and got out. Along the edge of the cemetery a section of unchecked growth allowed for a little bit of wilderness to establish itself. In this wild area, stands of cattails stood tall in the wet ground, while groups of asters and goldenrod lent a surprising jolt of color to the end of the day. Wild roses gone to seed gave off a fainter warm glow in their bulbous hips. It was a trio that only God could have put together, so I made a little bouquet of asters, goldenrod, and rose hips to bring to Dad. As I plucked the rose stem, my thumb met a thorn, tearing the skin and releasing a tiny drop of blood. A primal reminder that I was still alive, that my body’s blood still pulsed through its veins. It pricked a bit of my heart too, as I realized with full certainty that my Dad was not physically alive.

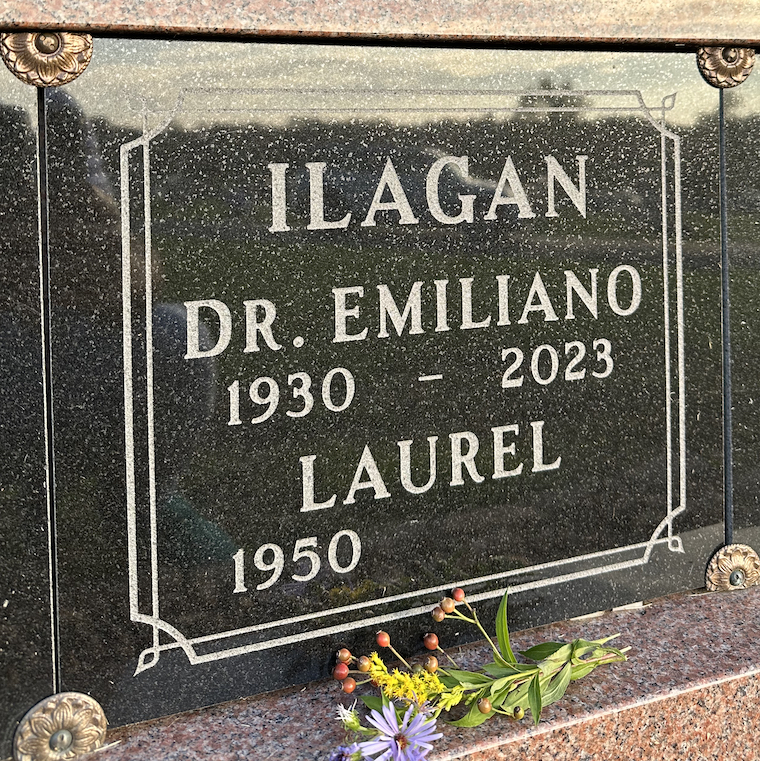

My little bouquet procured – no extravagant calla lilies or protea or hybrid roses – I got back in the car and drove back up the hill to where my Dad’s ashes were interred. Mom had already sent me photo of it, so I knew what it looked like, but it’s different when you see it in person. At the bottom of the columbarium, I found the engraved names of my parents. I ran my fingers over it, cool to the touch even in the dying light of the sun, and left the simple flowers beneath it.

Time twisted then, and I remembered my only trip to the Philippines, 27 years ago, when my cousin took me to the cemetery to visit her recently-deceased husband, and the markers of my grandparents. Seeing the Ilagan name there was jarring – not only because I never saw the Ilagan name anywhere in the United States, but also because it was on a gravestone in my father’s homeland. It struck me then, when I was only 21 years old, that one day I would be burying my own parents, and seeing their names engraved in stone. It was something that would haunt me forever after, right up until this present moment, as I knelt down and again felt the cold stone and the carved letters of my lineage. The moment I’d been dreading and fearing all my life was at hand, and though I’d always envisioned it blaring and announcing itself in frightening fanfare and debilitating noise, here it appeared in quiet, marked by distant birdsong, and the occasional rumbling of a car along the nearby road.

My Mom has said that she feels comfort visiting Dad here. For me, it was the opposite at first. As I backed away from their marker, I felt a profound sense of loneliness, a realization that my Dad was definitely not here. I knew his ashes were there in a piece of Wedgwood that once stood in our family home, I knew his name was forever embedded on the small square of stone I just touched with my own hands, and I knew his spirit lived within me, but in that moment I only felt his absence. It was the emptiness of being left behind, and as I got back into the car, I started crying.

Rather than fight it or try to collect myself instantly, I let it happen, allowing the grief to come over me in waves, catching the tears in the last tissues of a box I kept in the car for just such occasions. The sadness didn’t end, and the feeling of missing my Dad didn’t depart, but eventually the overwhelming sense of loss subsided, enough for me to start the car and begin the drive home.

Back to Blog