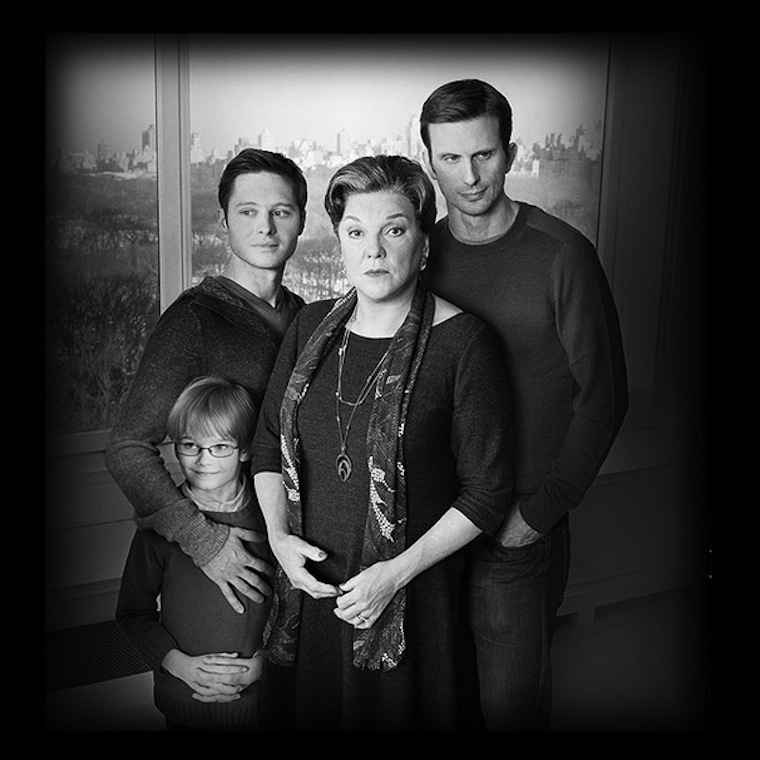

For our first show of the season, Mom and I saw, rather fittingly, ‘Mothers and Sons’ – Terrence McNally’s Tony-nominated play starring Tyne Daly. Mr. McNally has written some powerful plays over the years (notably ‘Love! Valour! Compassion!’ and ‘Master Class’ – which we had the fortune to see on Broadway during their original runs) and this one is no exception. If it doesn’t quite match the polish of those two standards, it may because this one is a little more raw, a little more urgent – something befitting the times recalled here. It helps that the play features a trio of fine performers, led by the amazing Ms. Daly, who gives a brittle, controlled, seething-just-beneath-the-surface performance as a monstrous woman (Katharine Gerard) still mourning the loss of her only child to AIDS. The early days of that plague are recalled with a distant but humane detachment. With each passing year, it becomes easier and easier to forget, and ‘Mothers and Sons’ may be McNally’s best efforts at seeing that that never happens.

Ms. Daly gives a subtle yet stunning turn as a lonely yet terrifying woman, filled with sly moments of black humor, hidden pockets of pathos, and one perfectly-rendered tear that, on this particular evening, happened to fall literally two seconds before the fall of the final curtain. That sort of precision is the work of a studied actress at the height of her power. Daly never lets her guarded heart show until the very end. In a few heaved sobs, she finds release, but it’s not quite clear if she’s found redemption. To Daly’s credit, you want to love some part of her, in spite of all her awfulness, and you almost do.

Anger plays a large part in this play, seen in the anger of her black fur coat, in her blood red dress, in her rigid black handbag that she carries with her about the apartment. Such fussiness is at odds with the relaxed, casual attire and attitude of her son’s former lover, Cal Porter, who picked up the pieces of his tragic past eight years after the death of his partner. As Cal, Frederick Weller has the emotionally-open roller coaster ride of the evening, veering from a hopeful earnest belief in people – showing a woman who has only hurt him the city of New York and drawing the audience into his comfortable life – before careening back into the dim days in which he lost his partner, and ending up somewhere ambivalently at peace with all that has happened.

Bobby Steggert as Will Ogden offers the idealistic and innocent view of the current generation, while their young son Bud (a precocious Grayson Taylor) offers a peek at the open-minded unaffected future. McNally offers many things to many people – the struggles of gay men and the AIDS crisis of the 80’s, as well as questions of age and gender roles, and new families being raised by two dads. In discussing Katherine’s past and the way she chooses to portray herself as being from Rye instead of Port Chester, New York, larger questions are raised and examined, particularly regarding secrets and the ways we pretend – or the ways we feel we have to pretend. It’s an ambitious work, that almost proves too much, threatening to dissolve beneath such broad historical strokes, but in the end it retains its heartfelt core, anchored by a spot-on group of actors who give these full-bodied characters conflicted, exasperated, heart-rendered life.

(After watching such a terrible mother mourn her son and the way she treated him throughout his short life, I was left feeling incredibly grateful for the woman who sat beside me in the theater, who loved me no matter what, and who did her best as my mother. We walked back through a misty night, to rest up for the next day’s surprise…)

Back to Blog